Saturday, 25 May 2019

Sifting through layers of history

The site of Foulden Maar, near Middlemarch. PHOTO: GREGOR RICHARDSON

Each autumn and winter, the blooms would die and sink to the lake bed.

Gradually filling in the 200m-deep lake, the layers of sediment preserved flowers, insects, fish and plant material that sank to the depths.

They created a record of life in the water and the surrounding rainforest, from 23million years ago.

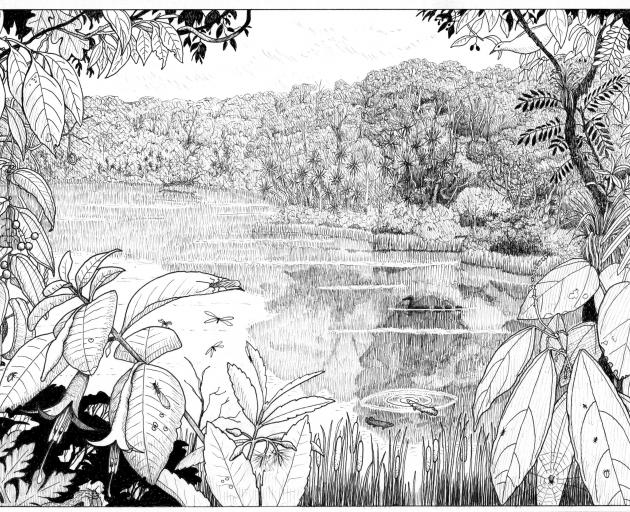

What Foulden Maar would have looked like 23million years ago. IMAGE: DR PAULA PEETERS

The area contains a smaller 5m deep pit, about the size of a tennis court, where researchers work finding fossils.

Another small pit can be found nearby.

Daphne Lee

About 100 different types of plants had been found, 200 different insects, three or four species of fish, and 40 different flowers from 15 different families.

"When a fish or insect or flower or leaf sank to the lake bed it would be covered by the next year's layer of diatoms, and because there was no oxygen there was no disturbance by predators, and no current disturbance because it was so deep," she said.

Thousands of fossils have been found, and researchers are still looking at only a small portion of the lake.

"Most of the fossils we find are leaves," Prof Lee said.

"Sometimes we are lucky enough to find flowers."

This fossil was taken from Foulden Maar, near Middlemarch. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

After learning about other maars overseas, Prof Lee realised water birds like herons would have brought them in in their bills.

Some of the fossilised fish would have perished when they swam too deep, unable to breathe in the lake's anoxic depths.

A fossil found in Foulden Maar. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

New Zealand's fauna was "much, much more diverse" than it is today, Prof Lee said.

She travelled to the site about once a month, and described it as "treasure-hunting".

"You have no idea what the next layer will have in it."

Fish fossils found include the oldest whitebait species in the world - and the oldest freshwater eel in the southern hemisphere, a recent discovery which is still being examined.

The majority of fossils taken from Foulden Maar are leaves, but 40 different flowers have been found. PHOTO: SUPPLIED

"It was probably completely frost-free for the forest growing around the lake," she said.

Preserved at the University's Department of Geology, the fossils were so abundant that anyone travelling to the site would be able to find one - but if they were not treated properly they would fall to pieces, Prof Lee said.

The current mining proposal for the site, from which Plaman Resources intends to take up to 500,000 tonnes of diatomite each year, has led to an upsurge in curiosity about the maar.

Taken from Foulden Maar. PHOTO: SUPPLIE

Research work at the site intensified massively after 2009, after researchers from the University of Otago received two Marsden Grant grants to work on the site.

They drilled down as deep as they could, 183m into the lake, through 120m of sediment and into the volcanic debris beneath.

Layers of the core are preserved in fridges at the university, where they are used as reference points for the scientists who visit the site to see what they can uncover.

No birdlife had been discovered in the lake so far, but dead bird fossils had been found in maar lake and Unesco site the Messel Pit, in Germany, so it was probable there would be fossils of birds among the layers, Prof Lee said.

Maar lakes were not uncommon, she said, but this was the only maar of its age in the southern hemisphere, filled with diatomite, and providing such an amazingly detailed climate record.

Hopefully, the lake would be preserved in its entirety, so not only scientists interested in climate change but also schoolchildren could visit the site, and extract fossils under supervision, Prof Lee said.

"That would be an absolutely brilliant thing. This is a dream, and it would have to be funded from somewhere.

"[The maar] would be a wonderful educational site for students, and it is, we know, a site of international scientific importance," she said.

"It would be wonderful if it could be preserved in perpetuity, for the scientific community, and public education."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comment here: